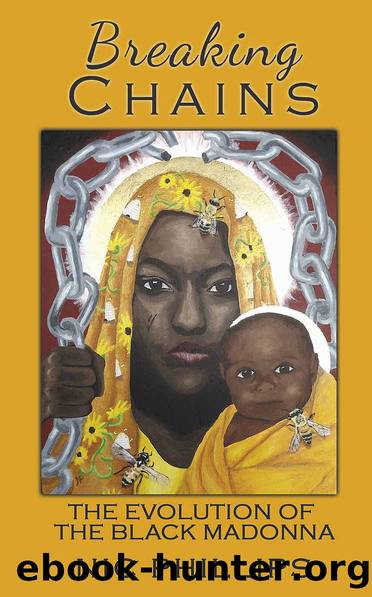

Breaking Chains: The Evolution of the Black Madonna by Nic Phillips

Author:Nic Phillips [Phillips, Nic]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Avalonia

Published: 2021-03-23T22:00:00+00:00

De-syncretisation

As Diaspora religions have become more globalised and moved towards recognition as âworld religionsâ, a de-syncretism movement has grown, particularly within Candomblé.[266] This has occurred in tandem with a Re-Africanisation movement which seeks to reunite descendants of Africans in Brazil with the languages and traditions of the Yoruba. Both movements reject Catholic elements of Candomblé and seek lost fragments of knowledge to reconstruct a supposedly pure African religion.[267]

Advocates of these movements are not in fact rejecting all forms of syncretism, just the Catholic parts of their religion. Sharing amongst Diaspora religions is encouraged as ââgoodâ syncretism between âsister religionsâ, allowing other Afro-Brazilian religions, such as Umbanda, to rediscover their African past and worldview through connections with, and ritual borrowing from other African-derived religions.â[268] This fulfils their objective of piecing together a lost African religion. However, this approach plays into the mythologised concept of a United Africa, the mythical homeland of Ginen, which itself arose from slavery. It does not acknowledge the diversity present in the western part of the continent from which these religions were drawn, and gives ammunition to those that criticise the âNagoizationâ of Candomblé, where focus is unequally placed on Yoruban heritage as representative of the whole of West Africa.

The cause for uniting disparate faiths under one Orisha religion has been driven by The International Congresses of Orisha Tradition and Culture (COMTOC) since their first meeting in 1981. Capone writes that âThe main discussion topics at these forums are tradition, standardisation of religious practices, and the fight against syncretism, topics that are common across different regional variants of the "orisha religion"â.[269] One of the most affirmative actions against syncretism came at the second meeting of COMTOC in 1983 where five famous mães-de-santo, priestesses of Candomblé, presented their manifesto. According to Capone:

âThis petition urged the end of Afro-Catholic syncretism â the association of Catholic saints with African orisha â and the rejection of all Catholic rituals âtraditionallyâ performed by Candomblé followers, such as masses attended on Catholic saintsâ days corresponding to orisha, the iyawó (new initiate) pilgrimage to churches at the conclusion of initiation, and the washing of the steps of Salvadorâs Bonfim Church.â[270]

Mãe Stella of Axé Opô Afonjá who led the petition said âA true religion is valued on its own account. It does not need to use another as a crutch to prove that it has valueâ, asserting Candomblé to be a true religion, not a âsyncretised sectâ.[271] She did not, however, agree with terreiros breaking with tradition and advocated de-syncretisation only, not Re-Africanisation.[272] For many terreiros, seeking religious authority in Africa would mean also giving up their power structures built over several generations. Worshippers were urged to seek spiritual purity in Afro-Brazilian traditions â just without the Catholicism.

Discussions on syncretism often revolve around the theory of the âmaskâ, largely developed by Roger Bastide in 1978, which asserts that African spirits were only hidden behind Catholic faces. His theory suggested that the descendants of Africans âcompartmentalizedâ their spirituality, being simultaneously Catholic and Candomblé, whilst not mixing the two, in a kind of âmosaic syncretismâ.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Becoming Supernatural by Dr. Joe Dispenza(8217)

Crystal Healing for Women by Mariah K. Lyons(7931)

The Witchcraft of Salem Village by Shirley Jackson(7275)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6796)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5782)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5371)

The Wisdom of Sundays by Oprah Winfrey(5162)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5122)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5008)

Fear by Osho(4740)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4720)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4473)

Rising Strong by Brene Brown(4459)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4357)

Sigil Witchery by Laura Tempest Zakroff(4246)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4137)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4130)

Real Magic by Dean Radin PhD(4129)